My Books

“Nobles’ work is singularly memorable, possessed of a sureness and lightness evidencing true poetic culture. All that is best in the current aspirations of poetry coalesces in his lines.”

— Donald Revell

A National Book Critics Circle Notable Book

Through One Tear

I had a dream.

And in that dream I dreamt that I was dreaming.

And in my dream I was dreaming

that I lay on a pillow sleeping,

not too soundly, which led me to have

a vivid dream. And in this dream I dreamt

that I had the covers on and I was warm

beneath the covers between the sheets.

And in this bed I dreamt that I was sleeping soundly

until the alarm went off (in that dream)

which I slapped off and fell back asleep,

into another dream. This dream was very strange.

It was a dream of multiple dreams, and each dream

was divided into a nation, and each nation

was a part of a continent, which was part of the planet,

in a universe of untold dimension.

But nothing was real; it was all a dream.

Some of the dreams began breaking up

like torn photographs of lovers dispersing on a lake.

And dreams began infringing on each other, like years,

until I did not know whether I was really awake

or awake in a dream. Then I dreamt it was a new century.

And then I really woke and staggered to the window.

Outside the window were people sleeping.

But they floated on a lake, dreaming.

The wet dead leaves looked like buildings in a dead city.

Their tiny tears blinked like desperate windows.

I looked through one tear and shivered.

I saw there the vacant streets, the broken vows,

the stark assembly of blackened steel. The moon-rippled

moon--disturbing--moving along so many ceilings,

ceilings almost white. And I watched dreams burning

like pieces of torn love (the wind painfully silent), whirling on the black lake

toward the center of the earth, its damaged inner ear.

First published in VOLT

Re-published in the anthology The Maine Poets, Down East Books

I walked across a tightrope all my life.

A line from Loss, my longest poem (470 lines)

Carnival Evening, 1886, Henri Rousseau

The Philadelphia Museum of Art

Nuclear Winter

When the sky fell, the earth turned blue.

The trees, the tenements, the cars and buses

soaked up the sky and changed from outside in, in color,

to blue. The children ran frantically in adult directions. My wife,

dressed fashionably in blue, took my hand and, with sadness

in her deep blue eyes, led me behind the house, down the long incline, and into

the woods. We waded in blue snow through blue trees.

An iridescent crow, blue, flew from a branch, and a fox

lay in our tracks, oblivious to our passing. He licked his blue fur

with melancholic eyes. The years pass very quickly with this earth.

In that time, we had two children, the son and daughter

we always dreamt of, and they knelt above us, like two granite stones,

ghostly figures praying, for the love of God, for what he had become:

a family moved by that one clear color, blue, beneath the blue snow.

First published in The Gettysburg Review

Re-published in the anthology Poetry 180, edited by USA Poet Laureate Billy Collins, and in The Maine Poets. edited by Wesley McNair, Maine Poet Laureate

Cowering in city basements,

shivering within the strong arms

of fear—oh crumbling cement,

oh dampness, the sickness,

be thankful for the darkness. A the sun,

broken by the branches,

lights up the path so delicately,

you look down through the stained

windows of a church

and step on the fallen, in silence,

the silence which is broken.

Section from the poem Thorn of Light

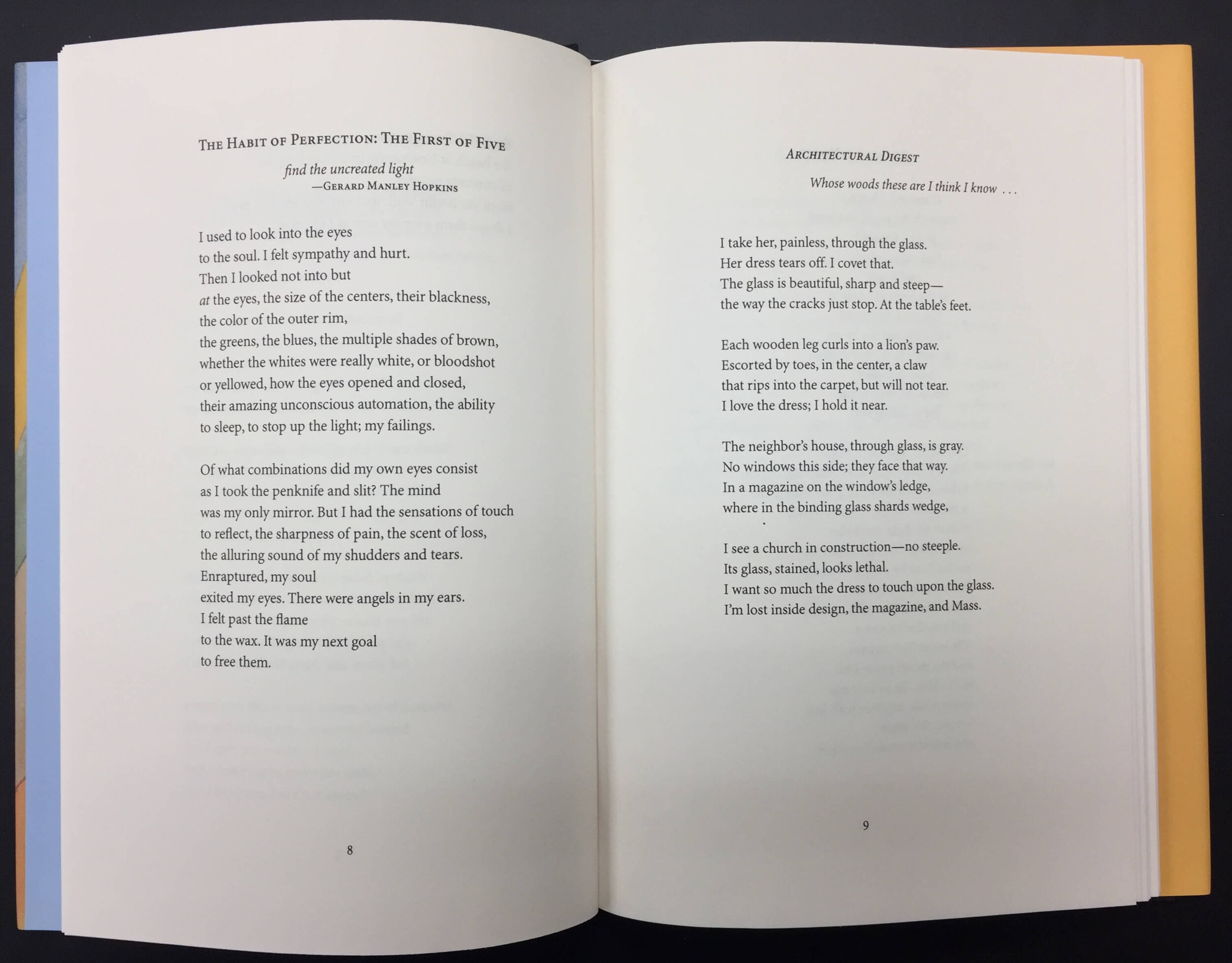

“The Habit of Perfection” first published in Boulevard.

“Architectural Digest” first published in The Paris Review (selected by Richard Howard).

To America’s Shore

A priest in the window. A street

with granite curbing lying on its side, uprooted

and washed ashore. Sidewalks

beautifully buckled from heavy frost. Streetlamps,

their cries of safety stopped, muffled in fog; they drop

their knives in scattered pools. Fissures in cool asphalt.

The late night passively takes this desire

that rises toward no one; helmeted, defiant,

pointing upward against the glass. The hour turns

and clicks off the only light. To what passion

is the soldier victim, the nation collapsing

upon itself in the dying century?

Determined, I walk these streets, my boot-

scuffs echoing like machinery, distant weaponry.

Reluctant voyeur, I am startled, repulsed

by my reflection: Homo sapiens in broken glass.

I whip the wind-rippled puddles with a broken stick.

The racing clouds uncloud the moon and crimson

skies reveal their magic. Oh, God of Night,

spring storms that claim and then reveal,

I revel in the mystery of my soul’s passions,

your dark mirrors glimmering with embers of torn red.

Everything is hopeless, useless, desperate. And yet,

I crave. For what? Saplings glisten.

Killed two birds with one stone.

We’re nothing now; both alone.

Broken branches, broken bones.

Black birds cross the telephone.

Black windows work black filament.

Membranes painfully reveal the night.

A woman stands there, each palm housed

in a cold pane, fingers outstretched against the wood.

She pours longing down the boulevard.

Red light falls into puddles, burns on each blade of grass.

And in the hunter-green flower boxes lie the tubers.

And in the gutter lies the book, its pages buckled

from a burst of rain. And the black glistening streets all weave

together, with houses, wires and windows,

down toward the sea.

A National Book Critics Circle Notable Book

“Poetry that is unconventionally metaphorical and gorgeously unorthodox in diction and approach”

– Dana Wilde

Fortune

This silver brooch is beautiful: spider-fine

filigree, bordered by two bands, and then a row

of circles, each its own creature, a coin-like design,

all tarnished, slightly dented, and twisted in a bow.

Unclasped from the pin, I unstick it from her sweater.

Some things are meant to come undone. But why

must everything appear in terms of money? Even this

seat, in which I stab the brooch, I had to buy,

smothered in smoke, from a bunch of brokers trying to better

one another, against a lover, for what they’d probably never miss.

But the hard-bought chair is beautiful, too. All rosewood,

except the cushion, which is an intricate scene

done in point, of a lion and his mate in somber pose. Should I

choose to die, theirs would be the place I’d mean

when I whispered for taut black trees and claw-torn deer

stitched in blue. And now one stag wears a bow.

I love the way the silver pin

slid so smoothly from the cashmere swell, and how I know

where the bow had been, and what forces steer

the fingers and the heart. That lions sin

is clearly in their eyes. There’s no doubt

this craftsman knew his task. Look at the back,

how the leaflets rise, but how the two flowers sweep downward in long pout.

Or how the wood so perfectly swerves to catch the light or its lack.

Even the arms, on which the drunken vines weave, were done

to perfection. Yet who was this carver? Did he create for one who loved as Lear

lingering long hours in the dark, dreaming of what sword to strike

the head off of a daughter? I unpluck the brooch and pull it near

to run along my face. The blackish silver has the features of a nun.

No faith can buy the tiny coins, the creatures in a spin, the web-like

tracery weaving in every fraction of an inch.

I take the seat and set the brooch down on my lap.

I touch the pin and feel each flower pinch

into my back, and wonder how the evening wraps

the hours, the decades, the seconds with a bow. Quietness

exerts its influence on both the lion and the vine.

Rosewood in every wood and from the blue the deer

leap into nonexistence for those who love to dine

in dark interiors, where black trees range the skies and skies express

the furniture, the magazines, the clothes removed. With love and fear.

First published in New Orleans Review

American Home

Chippendale, American,

with curved aborted leaf

and reeded spool, circa 1802,

this bridal bed, though pine,

retains its mahogany

reddish hue, a result

of thickened ox blood

and fresh New England cream.

The high heels, hushed

from their seductive click,

look innocent, unable to lure

with motion or the meaningful

turn.

I watched them fall,

each one alone, with seeming

intent, over the edge

of this tall

and vacant bed.

First published in The Gettysburg Review

There are 12 magazine-titled poems in The Bluestone Walk. Each of the twelve is written in a different style. And each involves different magazine, piece of furniture, and an article of woman’s clothing. Add in sensuality, longing, mystery and love — and hopefully the whole is weightier than the parts.

My wife Kelly always inspires me with her elegance and style. Her interests in the world of fashion certainly influenced the magazine poems in The Bluestone Walk.

First published in Boulevard

Contention

The base stones toe a rugged line.

Moss-stained and spud-round

from eruptions of weather, the upper

rows hold, steadied by chinks,

a dignified mass. Four ton of stone

contracts to four feet of wall.

Start at the pine, move north,

up-grade, there, to the narrow ones,

bark-stripped and dead.

My heartbeat rises and leans

its heavy jaw against my rib:

knocks bone and builds. I shrug it off

and lift another stone. Nothing

can break my will. The sledgehammer

shatters and bites

off perfect chunks to fill

all space. No light! No light!

The light that can be seen,

that should be seen, will be seen,

and gapped with stone. I knock

space off to fill space in.

The gray night, green-tinged,

cracks against this earth.

I’ll work all night, beyond

it, if it takes, beyond time.

Each thing lifts, hauls,

and rolls directly into place.

My muscles ache; my spirit, walled,

still loves. Love, with all

its waste, stacks

its labor against my work.

First published in William and Mary Review

A fieldstone retaining wall I built in Arlington, Massachusetts. I was born in Arlington, coincidentally in the same small hospital where poet Robert Creeley was born.

Sentences

The sledgehammer cracks

like my father’s heavy shouts

until the stone starts to break.

The sound then is different.

Only a thumb’s touch is needed.

The division is final.

Re-published in the anthology Take Heart, edited by

Maine Poet Laureate Wesley McNair

I learned how to build stone walls and walkways from my stonemason brother. I loved working with stone and working outdoors, but I was only a stonemason myself for a brief time. However, along with some granite and fieldstone walls, I did have the stonemason’s spirit long enough to build several stone-based poems from the experience.

Photos: Me unloading capstones for a granite wall. My daughters Lydia and Hadley helping me with a fieldstone wall. My wife Kelly at a granite quarry where I was picking up stone. My brother Stan and me taking a break on a bluestone patio we were building on Cape Cod.

Re-published in the Los Angeles Times

First published in Commonweal